RCEP and Pakistan

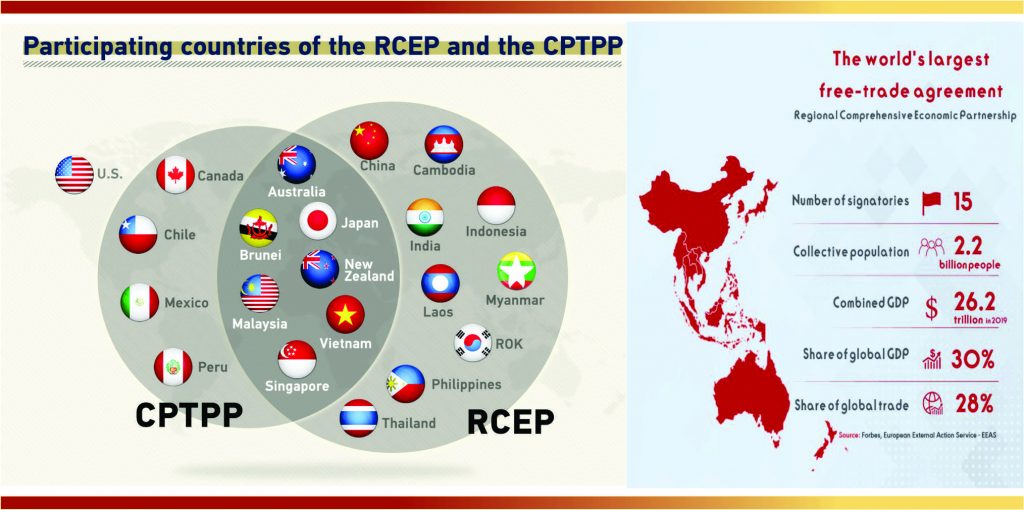

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is the world’s biggest trade bloc that includes fifteen Asia-Pacific countries — 10 ASEAN economies along with China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. It is larger than the European Union and the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement. RCEP countries comprise almost one-third of the world’s population and account for about 30% of the global economy.

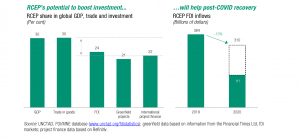

The agreement to lower tariffs and open up the services trade within the bloc does not include the United States and is viewed as a Chinese-led alternative to a now-defunct Washington trade initiative. It also solidifies China’s broader regional geopolitical ambitions around the Belt and Road initiative (BRI). The national income of RCEP members could increase by an estimated $186 billion annually. With greater market access in goods and services, the lower-income RCEP countries will become more competitive, attract higher investment levels and benefit from the relocation of industries. These countries will further harmonise into global value chains with simplified rules of origin.

As for Pakistan, the RCEP offers an opportunity that the country must grab because if Pakistan stays out of RCEP, then exporters would find it more difficult to sell their products to RCEP member countries — a market of 2.2 billion people with a combined size of US$26.2 trillion or 30% of the world’s GDP. With China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship project of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, RCEP presents a great opportunity to Pakistan for strengthening and broadening its economic linkages in the larger Asia-Pacific region. This is also in line with the broad market diversification strategy of Pakistan which is targeted to reduce its export dependence on EU and US.

In the recent past, as a share of total trade, Pakistan’s trade to RCEP member countries expanded rapidly from 2003 to 2012. Exports grew from 10.4% of total exports to 22% within the space of nearly ten years while the imports from RCEP member countries also witnessed the upward trend from 32.8% to 41.7% of the total imports during the same period.

Since the early 1990s, Pakistani policymakers have been making pronouncements about “Look East Policies”. While Pakistan established preferential trade agreements (with limited scope) with some Asean members such as Malaysia and Indonesia, it could not make any headway with the rest.

Since the early 1990s, Pakistani policymakers have been making pronouncements about “Look East Policies”. While Pakistan established preferential trade agreements (with limited scope) with some Asean members such as Malaysia and Indonesia, it could not make any headway with the rest.

Pakistan has had ongoing FTA negotiations with Singapore since 2005, Thailand since 2013 and South Korea since 2015. However, despite many rounds, there has been limited progress.

One major stumbling block in this regard has been Pakistan’s influential and highly protected industrial groups, which are opposed to further FTAs. They have somehow convinced the government that competing in global markets leads to de-industrialisation. However, this is not what Asean or other developing countries have experienced. The greater the integration they achieved, the more industrialised they became.

So, despite Pakistan’s protectionist outlook, it could have taken comfort that RCEP countries had up to 20 years of transition period to liberalise most of their tariffs.

Pakistan has to realise that its protectionist and isolationist policies have left it far behind. Its share of industrial production in its gross domestic product (GDP) has gone down from 26% to 20% and the share of exports from 13.5% to 7% during the last 10 years.

Historically, Pakistan’s economic and trade (mainly export) interests have been focused on European and US markets, with the recent exception of UAE and Afghanistan markets but these are very peculiar cases. This may have been due to ease of exports, market for Pakistani export products, i.e. textile, leather, rice, etc. and trade preference schemes such as the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP).

Historically, Pakistan’s economic and trade (mainly export) interests have been focused on European and US markets, with the recent exception of UAE and Afghanistan markets but these are very peculiar cases. This may have been due to ease of exports, market for Pakistani export products, i.e. textile, leather, rice, etc. and trade preference schemes such as the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP).

This has worked fine but one must not ignore the difference between market expansion in these traditional markets and eastern markets. There is recent wave of protectionism or at least slowing down of globalisation that is termed “slowbalisation” in western markets.

Moreover, these markets have moved towards services-oriented economies and with basic textile and agricultural commodities, Pakistani exporters may not really benefit from any growth in these markets.

On the contrary, the eastern markets are expanding at a rapid pace with huge demand for manufacturing and primary services sectors. In fact, the expansion in eastern markets is largely due to the positioning of these economies as manufacturing hubs for Western markets, and also due to growing level of indigenous demand.

With the exception of China, most of the expanding eastern markets are ignored by the trade policy of Pakistan. Even with China, with whom Pakistan has a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA), the true trade potential has not been harnessed yet, particularly when it comes to Pakistan’s exports to China.

With the size of market and expansion that China offers, one should have expected, by now, 10 times of current Pakistani exports – $2 billion per year. It may be good to have at least a brief assessment, by relevant ministries, on why this potential has not been translated from political statements to actual export numbers.

Beyond China, one hardly notes a meaningful commercial diplomacy by Pakistan in the eastern and Pacific markets. In order to change this status quo, the following five points may be considered for further deliberations on this topic:

a. Pakistan should seek an opportunity to join the recently concluded Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). RCEP is a free trade agreement among Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam, providing the largest FTA platform in the world. Joining the RCEP may be a long and complex process, but why not start exploring this unparalleled opportunity.

b. There is a need to develop and implement proactive and dynamic commercial diplomacy towards Central Asian and Russian markets. This geographic area has been almost ignored at the government level and a few hundred million dollars of annual exports are the result of sporadic private sector efforts. Recently, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) has become active in economic integration of its member states, and Pakistan being one of the members may play an active role in it. Another avenue to enter into these markets is exploring an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). The EEU is a recently concluded (2014) economic treaty with membership comprising Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

c. Map out the possibilities to join global supply chains that are generated/ routed through the eastern markets. There are plenty of opportunities even for primary and intermediate product exporters to integrate into those supply chains. This will naturally lead towards value addition and technology transfer in the longer run.

d. Develop the services sector, such as information technology, data and analytics, finance and other business process outsourcing, to enter into the expanding eastern markets. Some of the developed eastern markets such as Australia, Japan and South Korea have potential for low-cost offshore supply of such services.

e. Appoint new, or reassign out of mature Western markets, commercial diplomats in each of the eastern markets. They should be given specific and measurable export targets and serve as marketing representatives for introducing Pakistani supply capacities in these markets.

Pakistan must realize that a few least developing countries have ever been able to prosper, although they have such preferences from almost all developed and many developing countries.

In case of Pakistan, even if it isn’t a signatory to the RCEP, its companies can and should seize the trade facilitation allowed by the treaty through subsidiaries in one or more of the member countries. Pakistan should also encourage RCEP members, especially China, to veer towards integrating the benefits of CPEC into the RCEP. This can be done in several ways, including identifying service-sectors that would be appropriate for indirect participation in the RCEP, as well as the accelerated development of Gwadar and other infrastructure to complement the western rim of the RCEP member countries in terms of the movement of goods.

In case of Pakistan, even if it isn’t a signatory to the RCEP, its companies can and should seize the trade facilitation allowed by the treaty through subsidiaries in one or more of the member countries. Pakistan should also encourage RCEP members, especially China, to veer towards integrating the benefits of CPEC into the RCEP. This can be done in several ways, including identifying service-sectors that would be appropriate for indirect participation in the RCEP, as well as the accelerated development of Gwadar and other infrastructure to complement the western rim of the RCEP member countries in terms of the movement of goods.

It is time Pakistan adopts a more forward-looking approach. It must realise that there is a positive correlation between trade openness and growth. As Pakistan’s competitors integrate, their trade percentages rise while Pakistan’s isolation makes it lose its share. Our generation has seen our neighbouring countries lift millions of people out of poverty through trade. It’s time we follow them to do the same for our people. Subsidies and protection for a few at the expense of millions of poor people are not advisable.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.