Transitioning to Geoeconomics

While there is no denying the importance of Pakistan’s strategic location, the fact remains that this unique attribute has served to the country’s disadvantage, often sucking it into the vortex of regional conflicts and imposing choices on the country’s civil and military leaders that the country could not have done without.

From becoming part of the Western blocs i.e. SEATO and CENTO in 1955, to being in the vanguard of the US-led war against Communism in the 1980s to being the “most-allied ally” in American War on Terrorism (WOT), the costs in terms of the lives lost, economy hamstrung and the long-term impact on Pakistani society have been massive, often leading critics to question the wisdom behind sticking with geostrategic policy preference at the cost of the country’s permanent interests.

With every setback, the debate about the utility of geostrategic policy has made its way to the mainstream from the margins with more actors chipping in with their opinions in what is a candid conversation.

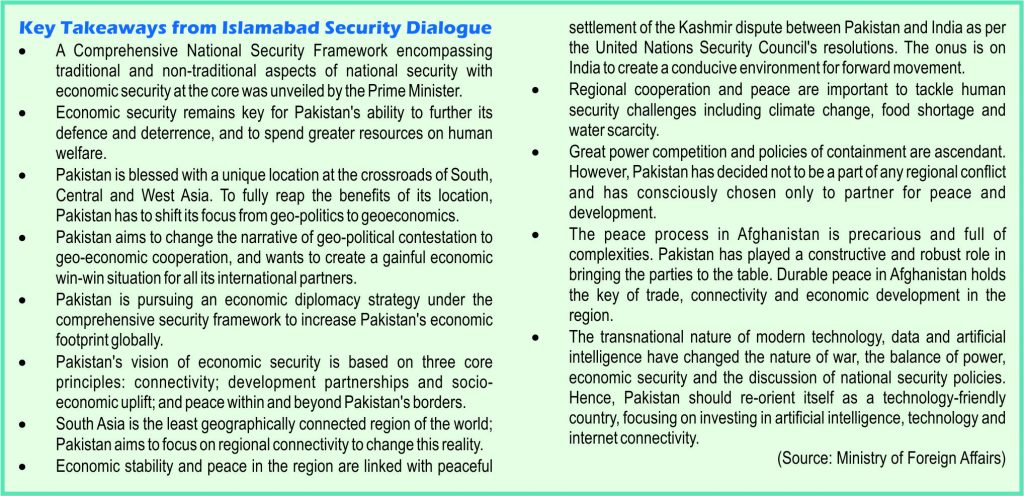

It is in this context that the two-day Islamabad Security Dialogue (ISD), held under the banner of the National Security Division in collaboration with five leading think-tanks of the country, represented the seminal initiative to revisit the security landscape and initiate a much-needed conversation on transitioning from geopolitics to geoeconomics.

It is in this context that the two-day Islamabad Security Dialogue (ISD), held under the banner of the National Security Division in collaboration with five leading think-tanks of the country, represented the seminal initiative to revisit the security landscape and initiate a much-needed conversation on transitioning from geopolitics to geoeconomics.

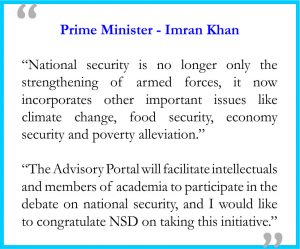

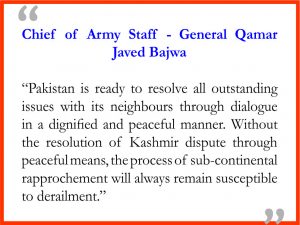

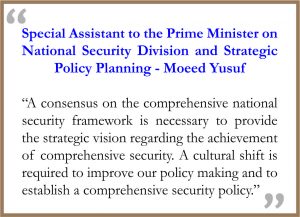

Addressed, among others, by the Prime Minister and the Chief of Army Staff, the speakers at the Dialogue analyzed the national security from the multipronged perspectives and proposed the way forward to address the emergent challenges.

The ISD represents Pakistan’s quest for a new strategic direction in a world dominated by the fast-paced changes that have a direct bearing on national security. The volatility of the world order is underlined by the lack of stable leadership as the international community forges regional alliances to protect their collective interests and push through their agendas.

Several factors can be identified that have shaped the thinking of Pakistan’s political, strategic and diplomatic community, necessitating a candid dialogue to rethink the need for pivoting to geoeconomic approach in the larger scheme of things. The following is instructive in this regard:

First, there is a marked global shift from the pursuit of geostrategic goals to prioritizing geoeconomic interests to unlock the vast potential that has been held hostage to a mindset locked in the outdated notion of strategic competition. Traditional modes of checkmating the rivals are losing their efficacy to the point of being outdated. The costs of continuing with such an approach are increasing by the day.

Second, the world is facing an uncertain future, a fact endorsed by the raging chaos, which is further underpinned by the global leadership crisis. The US may have elected ‘internationalist’ Joe Biden as the president, however, the deep sense of disillusionment with the global order is not going to go away any time soon.

Second, the world is facing an uncertain future, a fact endorsed by the raging chaos, which is further underpinned by the global leadership crisis. The US may have elected ‘internationalist’ Joe Biden as the president, however, the deep sense of disillusionment with the global order is not going to go away any time soon.

Nor will be the embedded thinking within a large segment of the middle-class white Americans that their country’s involvement in the global affairs at the behest of the Washington establishment has left them economically vulnerable and socially fragmented.

Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China may be advocating the idea of economic globalization with the UN at its core. However, the fact remains that Beijing is still far from replacing the US. The ensuing chaos is further undermining whatever remains of the world order.

The very concept of globalization that demonstrated the amazing potential to knit the global community into an interdependent whole is no longer a credible pillar of Western capitalism. It has been critiqued by the mainstream scholarship, not just the Left that is often scapegoated.

The reliance on the exclusive ability of the markets to correct themselves that forms the ethos of globalization has only resulted in further deepening the specter of inequality, with consequences that go beyond the economic factors. An economic system that does not incorporate mortality as one of the foundational principles in its structure is destined to frustrate hopes pinned on it. A depleting stake in globalization and its real and imagined failure to deliver economic justice has led to a popular disenchantment and loss of faith.

The reliance on the exclusive ability of the markets to correct themselves that forms the ethos of globalization has only resulted in further deepening the specter of inequality, with consequences that go beyond the economic factors. An economic system that does not incorporate mortality as one of the foundational principles in its structure is destined to frustrate hopes pinned on it. A depleting stake in globalization and its real and imagined failure to deliver economic justice has led to a popular disenchantment and loss of faith.

Third, linked to the global leadership crisis and the erosion of globalization is the failure of global institutions such as the UN to take the lead in protecting the collective interests of humanity. The implications of the gradual irrelevance of the UN system are grave, making the countries with less influence look for new partnerships and patrons to protect themselves.

The incoherent, disunited and often incompatible manner in which the world, particularly the powerful countries, behaved in the midst of the pandemic has pushed the world bodies such as the World Health Organization further to the periphery. There has been little concern that the approach employed at the cross-purposes has only been detrimental in terms of loss of precious lives and the halting of the global economic activity.

Fourth, as the Biden administration rushes to strengthen partnerships and reassert the claim to global leadership, the world is increasingly paranoid by the prospect of a new bout of the cold war with China. The recent Quadrilateral Security Dialogue meeting, the first such virtual interaction between the member countries after Biden took over, represents the US effort to contain China in line with President Bush’s formulation of ‘with us or against us’.

Fourth, as the Biden administration rushes to strengthen partnerships and reassert the claim to global leadership, the world is increasingly paranoid by the prospect of a new bout of the cold war with China. The recent Quadrilateral Security Dialogue meeting, the first such virtual interaction between the member countries after Biden took over, represents the US effort to contain China in line with President Bush’s formulation of ‘with us or against us’.

The opposition to China enjoys bipartisan support across the party divide in the US. The tactics and approaches to deal with China may vary between Democrats and Republicans but there is a consensus that China is America’s greatest rival and an economic and military competitor. This explains why the US has been a determined critic of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and has entertained suspicions about CPEC, calling it a “debt trap” for Pakistan.

In the foreseeable future, as the competition deepens, the Sino-US relations are likely to be defined by the politics of “blocs”, sucking up space for countries like Pakistan.

Fifth, the global challenges are equalled, in their intensity as well as implications, by a prevalent sense of chaos and meltdown that countries are experiencing from inside. As economies shrink and internal fault lines widen, systems are coming under enhanced stress.

The crises such as the corona pandemic have added to the worries of the governments as they take measures to keep the engine of the economy running and protect the poor through cash handouts and other means.

A surge in populism, a trend in ample evidence worldwide, poses a challenge to the legitimacy of governments and the status quo. The disparity between increasing populations and decreasing resource base, particularly in developing countries, has further added an impetus to restlessness and a sense of disarray.

Sixth, Pakistan is located in a region that has failed to realize its economic potential due to the prevalence of conflicts. The wars in Afghanistan, the current one being the longest in American history, have had dire consequences for Pakistan in a variety of ways.

As the confusion persists about the American’s withdrawal plan from Afghanistan, the fate of the Doha Peace Accord remains delicately poised. The possibility of a new and more deadly war breaking out becomes a near certainty. There are too many dots to be connected to allow peace a chance, while the deadline of May 1 approaches fast.

As the confusion persists about the American’s withdrawal plan from Afghanistan, the fate of the Doha Peace Accord remains delicately poised. The possibility of a new and more deadly war breaking out becomes a near certainty. There are too many dots to be connected to allow peace a chance, while the deadline of May 1 approaches fast.

Pakistan has, no doubt, played a principal role in the successful clinching of the Doha deal as stated by the Army Chief. However, it has every reason to be prepared for the post-May scenario in Afghanistan.

Seventh, India is undergoing a historic transformation under Modi’s nationalistic government. The illegal and immoral annexation of the Indian-Occupied Kashmir has set into motion a train of events that is exposing the reality of the world’s largest democracy. New Delhi’s increasing and palpable tilt towards fascism has not gone unnoticed in the world capitals. The downgrading of India’s status from free to partly-free democracy by the Freedom House report is the latest indictment of Modi’s India.

These profound changes on the global and regional landscape have opened up a historic opportunity for Pakistan. The country’s successful fight against terrorism established her resilience and a strong sense of purpose in defending her territorial sovereignty. It is only natural that a more determined, and self-assured Pakistan articulates its future vision in the light of the prevailing realities, a vision that is grounded in the promise of an egalitarian and Islamic welfare state.

These profound changes on the global and regional landscape have opened up a historic opportunity for Pakistan. The country’s successful fight against terrorism established her resilience and a strong sense of purpose in defending her territorial sovereignty. It is only natural that a more determined, and self-assured Pakistan articulates its future vision in the light of the prevailing realities, a vision that is grounded in the promise of an egalitarian and Islamic welfare state.

The Islamabad Security Dialogue is like a nation talking to itself in a frank manner about the aspirations of its teeming millions and having the clarity to chart the way forward. This constitutes a good beginning. However, a lot more needs to be done to translate the policy intent into reality.

First, the transition of Pakistan’s foreign policy outlook to geo-economics will take time to materialize and as they say, the devil often lies in details. The possibility of opposition to this proposed change in direction from the quarters that benefit the status quo cannot be ruled out. Therefore, it is all the more imperative that a strong political will informs the transition that does not allow the setbacks to throw spanners in the works. The vested interests will not be okay with this bold policy move and would want to keep the things the way they are. Thus defeating their machinations will require strong will.

Second, Pakistan’s economic interests have suffered for want of the policy continuity caused by the political instability. So, if Pakistan has to successfully negotiate its way to geoeconomics, it must have the consensus of all stakeholders. The Islamabad Security Dialogue might have shown the way forward, what is required is building necessary consensus around the concept by ironing out differences. The best forum to spearhead the consensus-building effort is the Parliament by virtue of its representative character. The initiative can be further complemented by the passage of Charter of Economy to provide the country policy space to implement long-term national reforms to put the economy on the path of recovery, and sustainability. It has to be understood that without developing sound economy, the country will fail its 220 million people.

Second, Pakistan’s economic interests have suffered for want of the policy continuity caused by the political instability. So, if Pakistan has to successfully negotiate its way to geoeconomics, it must have the consensus of all stakeholders. The Islamabad Security Dialogue might have shown the way forward, what is required is building necessary consensus around the concept by ironing out differences. The best forum to spearhead the consensus-building effort is the Parliament by virtue of its representative character. The initiative can be further complemented by the passage of Charter of Economy to provide the country policy space to implement long-term national reforms to put the economy on the path of recovery, and sustainability. It has to be understood that without developing sound economy, the country will fail its 220 million people.

Third, narratives are the key to diluting opposition and making policy changes acceptable to the people. It is for this reason that the countries spend their resources and time in reaching out to people and winning over their support by explaining the wisdom behind the changes in key areas. The people of Pakistan need to be educated on the likely benefits of a transition to geoeconomics including how their material conditions will improve if the country can manage to unlock its economic potential. A policy paradigm has a greater chances of success if it is owned by the people at large, for they can see their own fate intertwined with it.

Through CPEC, Pakistan has begun its journey towards geoeconomics. It needs to stay invested in the process to let its benefits accrue to the teeming millions.

The writer, a Chevening scholar, studied International Journalism at the University of Sussex and regularly contributes to The News. He can be reached at: amanatchpk@gmail.com

Twitter: @Amanat222

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.